Lifelong creativity: ‘A Complete Unknown’ and Bob Dylan’s ‘other things’

As a movie, how does it feel? Pretty great. But "A Complete Unknown" also evokes thoughts of what it means to stay creative long after the first flush of success.

The spellbinding new film “A Complete Unknown” starring Timothee Chalamet is a conventional musical biopic in the sense it does its routine job of charting Bob Dylan’s rise to fame in the early 1960s in New York.

It also belongs to an obvious lineage of such films. Director James Mangold previously helmed the Johnny Cash “Walk the Line” feature in 2005. All the critical and commercial acclaim of 2018’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” rejuvenated the Queen catalog and triggered a new wave of musical cinema.

But more than any other movie I’ve seen, “A Complete Unknown” is one where the script is embedded in the songs rather than having songs woven into a script. There are relatively few extended scenes, set pieces, or monologues. The caliber of the actors and quality of their original musical performances—particularly Chalamet’s uncanny inhabiting of Dylan, Ed Norton as Pete Seeger, and Monica Barbaro as Joan Baez—elevate the narrative. But by its very design the movie almost plays out like one fluid extended folk song.

Dylan himself apparently approved the script line by line, although he lacked control over the final cut. As a longtime Dylan fan who’s attended a dozen or more of his concerts stretching back to 1993, I wasn’t expecting complete historical accuracy. There will be the usual horde of Dylan scholars to remind us of every misplaced recording session or article of clothing.

The New Yorker knocks the movie for lack of period detail, claiming “the life of the artist is reduced to a just-so story of soaring above banalities and complications.” But in the main I’d say “A Complete Unknown” gets the spirit exactly right. Any timeline twisting or recontextualizing feels more like a valid artistic concession aimed at capturing the larger truth.

The central tension of the plot is Dylan “going electric” in 1965 at the Newport Folk Festival, departing from the lineage of Woody Guthrie and Seeger to chart his own rock ’n’ roll path. It’s based on the book “Dylan Goes Electric” by Elijah Wald.

In the opening scenes, Dylan tumbles out of the back of a station wagon in 1961 as a complete unknown to New York. By the end we’re left wondering whether Dylan knows himself as a person inhabiting everyday life, or if we as his audience have ever truly known him. Inscrutability always has been central to the Dylan mythology, and this film does just about the best job of confronting the man behind the sunglasses without pretending there’s one true and profound answer to what motivates the only musician awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

21st century Dylan: ‘I can do other things now’

But what I’m really here to talk about is what I hope can be amplified with all the publicity around the film. Dylan, like any icon, can’t escape public fixation on his charismatic early phase that cemented his legacy. Yet in the last 25 or so years he has produced some of the best music of his entire career. Inscrutable as he is, this much we know: Dylan, 83, is a lover of his craft who has spent a lifetime nurturing his creative muse, and that has paid off with a substantial—if messy and inconsistent—body of work in the 60 years since “Like a Rolling Stone.”

I always refer to the late Ed Bradley’s 2004 “60 Minutes” interview with Dylan as a tidy representation of this late-career renaissance.

“I don’t know how I got to write those songs,” Dylan said, commenting on his early ’60s burst of folk-rock classics.

“What do you mean you don’t know how?” Bradley asked, leaning in.

“Well, those early songs were almost magically written. … Try to sit down and write something like that. There’s a magic to that, and it’s not Siegfried & Roy kind of magic. It’s a different kind of penetrating magic. And I did it at one time.”

“You don’t think you can do it today?”

“Uh-uh.”

“Does that disappoint you?”

“Well, you can’t do something forever, and I did it once, but I can do other things now.”

“Blowin’ in the Wind” as a near-perfect song probably will outlive everything ever written on Substack. But I hope there’s space during Oscars season for more recognition to flow to Dylan’s “other things” beyond the new film. In another interview he even referred to his latter-day method as assembling songs on a musical grid. The difference between that workmanlike approach and his “penetrating magic” of the ’60s almost tells you everything you need to know about Dylan the artist: There’s never one way to channel inspiration. The only certainty is that you must plow ahead with your craft and keep toiling.

Some people date Dylan’s creative revival to 1997’s “Time Out of Mind.”

It definitely was underway by 2001’s “Love and Theft,” an album I’d rank firmly among his top five of all time.

He’s since released at least nine more new albums, including 2020’s epic “Rough and Rowdy Ways.” The young Dylan voice Chalamet captures so well in the new movie is one thing, but for my money, the more ragged and weary Dylan we’ve heard in the last 25 years establishes him as one of the best singers in the history of recorded music. It’s not about the biological limits of his vocal cords; it’s about the incredible emotional nuance and narrative range he evokes with such a beautifully flawed instrument.

From 2006 to 2009 Dylan also was host of his own “Theme Time Radio Hour” on satellite radio, exploring much of the musical catalog and history that inspired him.

He released a fun, tongue-in-cheek Christmas album.

He has kept performing in concert on his “Never Ending Tour” where he treats his songs not as museum pieces but as clay to mold according to his whims.

He’s never been too precious about profiting from his brand. He has helped to sell everything from lingerie to his own whiskey blend.

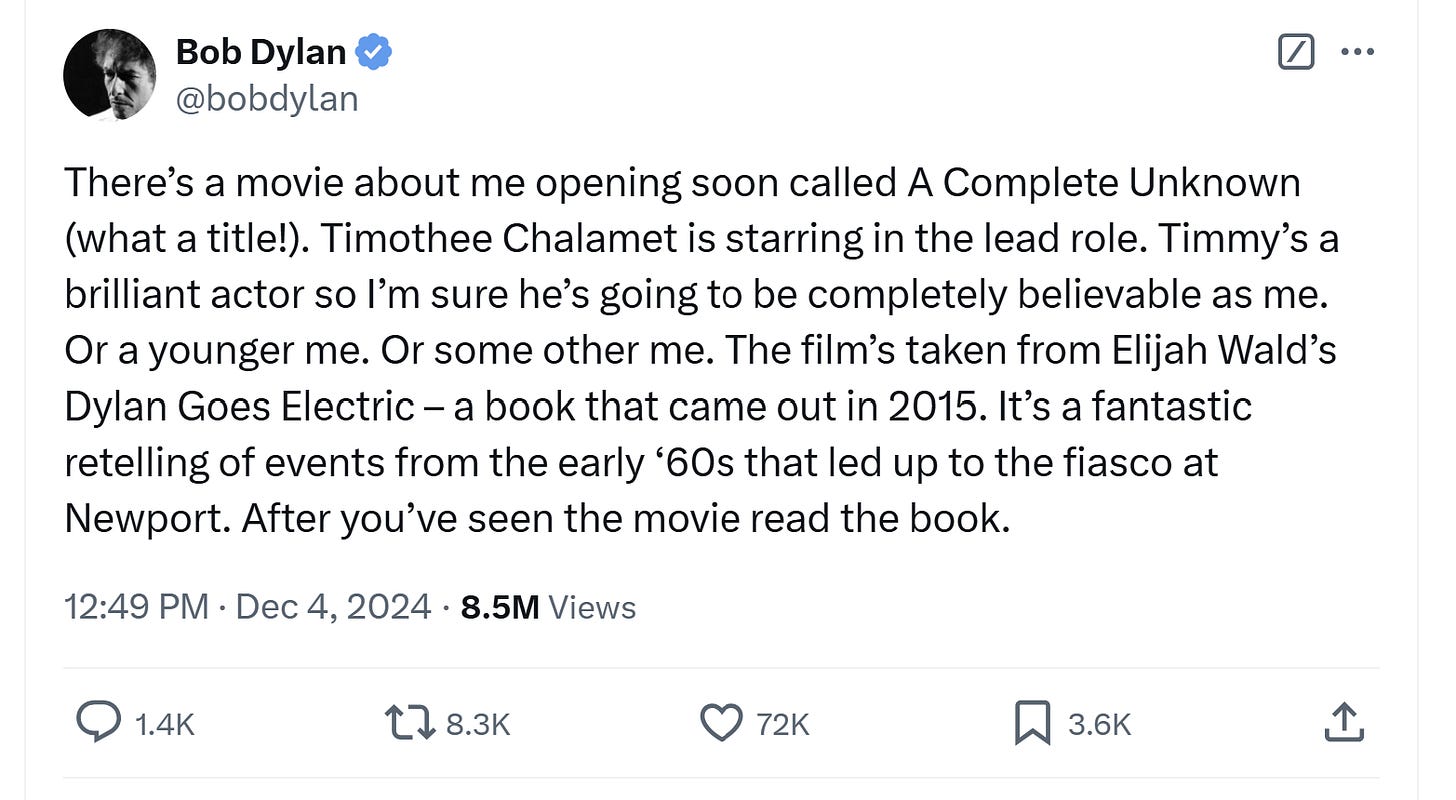

This year he even seemingly took over his own X account.

We Americans love nothing more than witnessing a rocket ride into the celebrity stratosphere. We love it even more when it’s packaged with the inevitable fall from grace and eventual hard-won comeback, where the hero has learned to be a better and more resilient person.

True to its subject, the new Dylan biopic gives us none of this straight. We get to enjoy some of the rocket ride, but its trajectory leads straight into the center of Dylan’s own artistic mind. The film leaves us only with a sense of mystery and more questions. (You know where the answer is; I’ll avoid the obvious pun.)

All I can offer is a sequel of sorts: Dive into the Dylan catalog starting circa 2001. The movie’s events of 1965 point the way to what we still can enjoy today from an uncompromising—and arguably unknowable—artist.

The Iowa Writers Collaborative has grown to include more than 50 members and a Letters From Iowans column. Each member is an independent columnist who shares two things in common: They have made a living as a writer and are interested in the state of Iowa. Subscribe to the main account for a convenient way to be notified each Sunday about most posts by most members. You can support individual members according to your unique interests by becoming a paid subscriber to any newsletter. We are also proud to be affiliated with Iowa Capital Dispatch, where some of our content is regularly republished.