Salomone brought us together as one city under a groove

Sam Salomone welcomed everybody to join the jam--all the more evident in the outpouring after his death.

The “basement hang” was a fixture in the life of the late Sam Salomone.

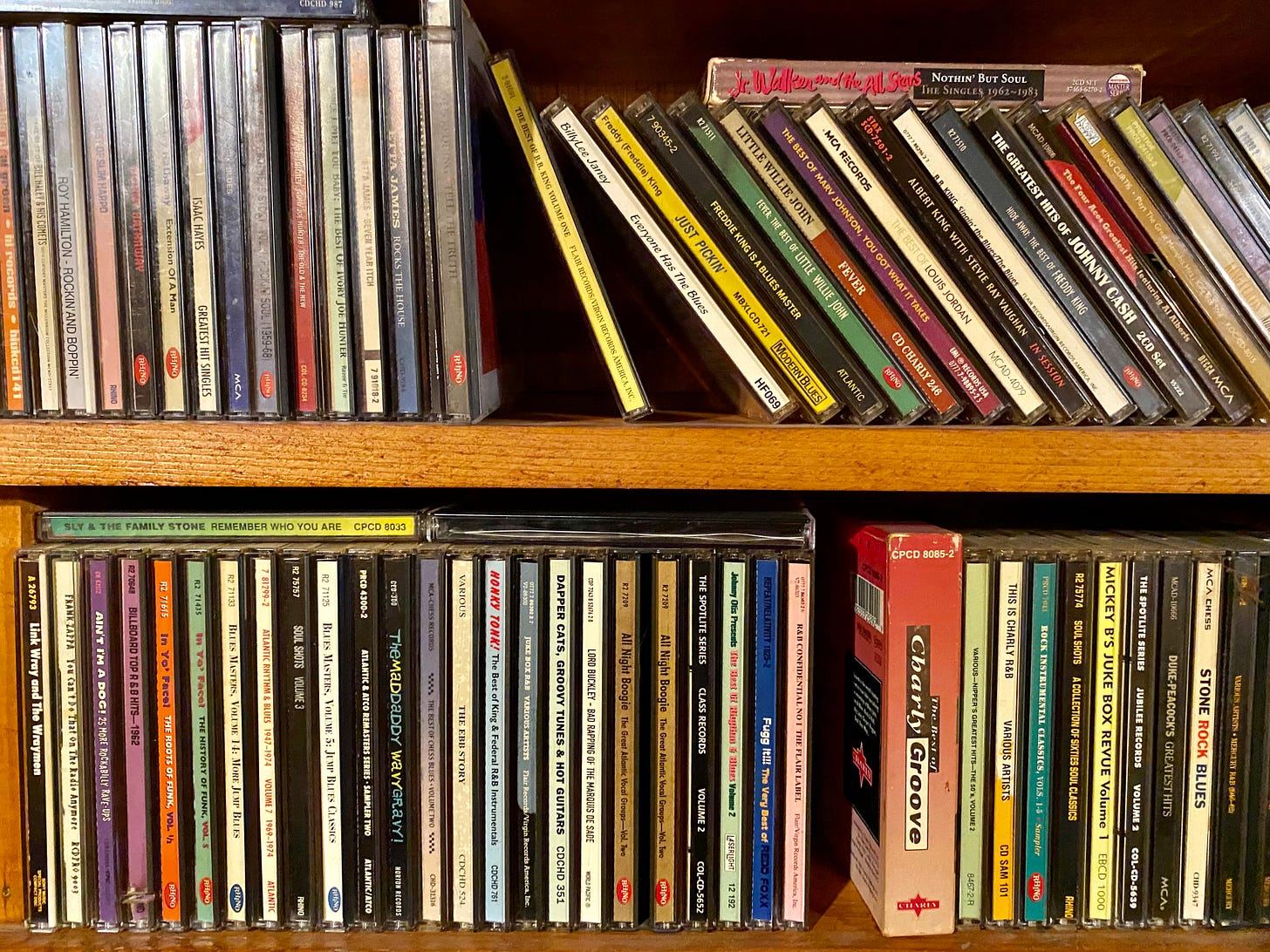

The beloved and revered Des Moines jazz-blues-funk-everything organist would invite friends to join him in his basement refuge to hang out, kick back, and comb through thousands of LPs, 45s, tapes and CDs stored in every nook and cranny.

Salomone died Nov. 29, just three weeks shy of his 80th birthday.

To pay tribute to Salomone I convened a handful of his friends and fellow musicians in that familiar space, surrounded by the artists and songs he loved. I knew the setting would spur stories.

So I descended into the wood-paneled basement. The faces of James Brown, Miles Davis, Frank Sinatra, Dizzy Gillespie and other icons looked on from the walls.

“He knew where every record was,” said Linda, his wife of 51 years. She gestured at the stacks in all corners—even cluttering the laundry room. One box nearby held, in alphabetical order, “Dr. John to Frankie Ford.” Salomone was known to listen to music at any hour.

“Without him here, the house is too quiet for me,” Linda said.

I visited the basement the day after a loud and boisterous afternoon inside the conference rooms of the Des Moines Botanical Center. Salomone’s memorial, appropriately enough, wasn’t a solemn ceremony. The four-hour jam session featured a rotating lineup of musicians whom he had influenced or accompanied.

Gary Jackson sang an aching blues ballad. Del “Sax Man” Jones wailed a solo. The reception table featured a guestbook and free copies of Salomone’s CDs, “It’s Never Too Late” and “VooDoo Bop.”

The centerpiece was Salomone’s worn yet majestic Hammond B3 organ directly in front of the stage. The instrument was bedecked in flowers and topped by a black-and-white portrait of its late owner.

A suburban Chicago native, Salomone first got his hands on a Hammond in 1965.

"I wasn't gifted," Salomone told me in 2005 about learning to play. "Sticking with it, not giving up, that's what it is. Someday you're probably going to get it right."

He strayed to Kansas City and the coasts early in his career but eventually returned to Des Moines to rely on steady work and raise his daughter.

Salomone forged key partnerships with fellow Des Moines musicians such as Dartanyan Brown.

Brown said that he and Salomone are the only two musicians inducted into three local halls of fame: the Iowa Blues Hall of Fame, Iowa Rock ’n Roll Hall of Fame, and Des Moines Jazz Hall of Fame. Brown has written about how the capital city’s progressive—and sometimes racially integrated—music scene of the late ’60s and early ’70s nurtured him, Salomone, and their entire generation of creators:

“From 1967 until 1978 the Des Moines scene was monstrous because country, blues, swing jazz, free jazz, rhythm-and-blues, and folk musicians all jammed, recorded, and interacted with each other in dozens of jam sessions where seasoned jazz pros jammed with rock musicians who may have been less capable technicians but who were dead on in connecting to the burgeoning young audiences of the coming ’70s who were hungry for ‘relevant’ music.”

“He and I had some insane musical adventures as music became a little less acoustic, a little more electric,” Brown said this week.

Salomone had been weaned on rock and doo-wop as well as blues and jazz and above all seemed to prize the groove that cut across genres. That expansive sensibility bubbled up in the basement reminiscence.

Saxophonist Nathan Peoples—who flew back from Colorado for the memorial—grew up awed by Salomone, whom he heard Monday nights at Court Avenue Brewing Company in downtown Des Moines. He later gigged there with his mentor, sharing a ritual shot of Courvoisier at the start of their third set. The two also toured together in an incarnation of Bob Dorr’s Blue Band.

Don “T-Bone” Erickson cherishes memories of downtown blues festivals and band battles with Salomone.

Accordionist—yes, accordionist—Abe Goldstien once ran a record store called Elysian Fields next door to Drake University, where Salomone was a regular customer. While Salomone leaned into funk and fusion, Goldstien, then as now, was a staunch, unrepentant disciple of the avant-garde.

I grabbed a random record off the basement shelf that turned out to be a title from 1970s fusion group Weather Report.

“Oh, there’s one we would argue about,” Goldstien said with a smile. “He loved Weather Report.”

The first tune Salomone learned to play, according to friend and fellow musician Dave Altemeier, was Horace Silver’s “The Preacher.”

“I learned a lot about playing bass from the way he played organ,” Altemeier said of Salomone.

At this point I must recognize that what I had planned as a brief tribute to Salomone is running long. Blame it on a severe lack of editors across Substack to rein us in. At the very least, let me break up the text with a transition and subheadline. I’ll borrow one of Salomone’s pet phrases uttered to audiences at the end of a first or second set:

“We’ll be back in a flash with some more trash for your cash.”

Salomone wrote the soundtrack of our lives.

For me, Salomone at first was a disembodied voice over the airwaves.

Before I witnessed him perform or knew anything about him, I listened to his radio shows in the early ’90s on alternative station KFMG (then at 103.3) while driving across Iowa. The name of the show, “Cookin’ With Sam” (and another, “Jazz Gumbo”), referred to his melting-pot musical taste. But it also offered a literal nod to his sideline career as a chef at former downtown Des Moines restaurant the French Quarter.

I still almost picture the stretch of road when I first heard Salomone play tracks from the James Brown “Star Time” box set, or when he introduced me to the irresistible groove of Stevie Wonder’s “Boogie on Reggae Woman.”

Salomone caught my ear as a curious and savvy musical curator. Even better, I couldn’t immediately fit him into a box—according to genre, race, or any measure.

He continued his radio career through the latest incarnation of KFMG as a low-power FM station at 98.9 in Des Moines. Ron Sorenson, who owned the former KFMG and is general manager of today’s version, praised Salomone’s deep sense of rhythm that seemed to invite everybody into the jam.

“He was always so much in the pocket,” Sorenson said. “He was hardly ever too hip for the room.”

Salomone was one of those characters who threads themselves through the shifting cultural landscape of a city. As residents swarm into all the barrooms, restaurants, and music halls, characters like Salomone write the soundtrack of our lives—no matter whether we stop to recognize it at the time or only after they’re gone.

Salomone’s father owned and operated the Tick-Tock Lounge in Waterloo, and the organist son played in countless venues throughout the Des Moines metro:

Green Jeans.

Café di Scala.

Louie’s Wine Dive.

Yacht Club.

Noce.

And so on.

Singer-keyboardist Jesse Villalobos, 45, who now lives and works in New York but returned for the memorial, first met Salomone as a teenager. Soon he was invited on stage to sing. The he stepped into his first basement hang. The closeness of his friendship with Salomone is shown by his inheritance of the hallowed Hammond B3.

Villalobos saw his mentor persevere through illness in the last decade. Salamone battled renal failure and coped with regular blood infusions.

After one stint in the hospital, Villalobos encouraged Salomone to start playing again—only to see the veteran musician break down in tears over how he had tried in vain to marshal the strength to play. Yet he eventually fought his way back to sit at the keyboard once again.

By all accounts, Salomone set high standards for himself and all other musicians. In the middle of a gig he might swear at his hand, as if blaming the appendage for what he perceived as his bad performance.

Goldstien remembers Salomone educating scores of young musicians through the Community Jazz Center. During one of those jam sessions, the students grabbed Goldstien because Salomone was slumped over his piano. Everybody feared the worst. But the cause turned out to be musical, not medical.

“Man, I hated that solo I just played,” Salomone said as he lifted his head.

Salomone kept gigging nearly until the end. His final show—fighting through nausea—was on a Friday in November at the Cave in downtown Des Moines.

The encore of Salomone’s memorial jam at the Botanical Center featured a New Orleans-style second line parade to roll the Hammond organ out of the venue and into the waiting cargo van—one final load-out.

If that Hammond could talk, it would tell stories of being lugged up and down flights of stairs for gigs. It would remember a 1999 show at Hoyt Sherman Place, where one of Salomone’s heroes, Jimmy Smith, put it through its paces and made ribald jokes after receiving the key to the city from the mayor.

Salomone credited a 1967 Smith concert in Chicago for revealing to him the crucial organ technique of balancing bass with the left hand and melody with the right.

Some of Salomone’s ashes may make their way down the Mississippi River to the city that may best represent his musical and culinary ideals, New Orleans.

Meanwhile, the Hammond is settling into its new home at Villalobos’ apartment in the historic Bed-Stuy neighborhood of Brooklyn. The Salomone disciple looks forward to spending a three-month spring sabbatical developing his chops on an instrument whose sentimental significance outweighs its 400 pounds.

Salomone became increasingly philosophical and spiritual in his final years, Villalobos said, dwelling on the true purpose of live music—basically questioning why he had spent all those years peddling the songs he loved.

I think it’s about connecting, Salomone finally determined. That’s what it all comes down to.

Thanks for the tribute to a true Iowa gem.

Nice retrospective memorial Kyle! Sam was a musical shaman. A healer, a helper. His legacy was exponetial, as the ones he taught, taught the next ones and so on and on and on.